Part 4: Dormitorium

07.12.2024

Exhibition view Volume III, Part 4: Dormitorium, December 2024. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg

Exhibition opening Volume III, Part 4: Dormitorium, December 2024. Photo: Greta Windfuhr

Exhibition view Volume III, Part 4: Dormitorium, December 2024. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg

Wooden pillow, 1930, anonymous artisan, Shaan Xi (China), private collection of gerlach en koop. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg

We welcome you to the fourth chapter of The Last Terminal, Volume III, titled Dormitorium, a continuation of two parallel long term solo exhibitions: Om zes uur? Slapen. by gerlach en koop (2024–) and Paintings by Lisa Ivory (2024–2025).

Paintings

Lisa Ivory (2024–2025)

Lisa Ivory’s paintings point to an evolving story with a seemingly clear narrative arc yet the stories do not easily yield to identifications and sympathies. They undermine our certainties about where we are in relation to what we are looking at. They lead one into a painterly universe; a shadow world, a natural habitat for nudes, skeletons, and domesticated monsters.

In Part 1: Beating Death With His Own Arm, we presented two paintings titled Tourist In Your Town and Love And Communication.

In Part 2: Errors, we presented three new paintings titled Foal Phantom, Hard Times, Call It Something Nice.

In Part 3: The Recipient, we presented three new painting titled Outside Love, What the Goat Saw, A Summer Evening.

In Part 4: Dormitorium, we will present a new series of paintings.

Om zes uur?

Slapen.

gerlach en koop (2024–)

How unpredictable is sleep. It is not a skill you can acquire or learn. The sleepless are powerless. Sleep is granted, it just cannot be forced. The only thing you can do is imitate your own sleeping body. Restage the conditions of the night before when it worked—same position, same routine—hoping that at some point the copy will again be convincing enough to merge with the original.

In 2020 gerlach en koop displayed works by other artists in an exhibition titled Was machen Sie um zwei? Ich Schlafe. at the GAK, Gesellschaft für Aktuelle Kunst in Bremen, Germany. In this exhibition they tried to approach the elusive phenomenon that is sleep from both sides, with works that either correspond to the disintegration of falling asleep or the reintegration of waking up.

Throughout the year a restaging of this rather unusual solo-exhibition will unfold in Rib. What was stretched out in space in Bremen will be stretched out in time in Rotterdam. Small gatherings of works each time, four or five, six at the most. Trying to find a position that worked before, trying to merge with the original, like an insomniac.

For the fourth gathering gerlach en koop decided to not cover the wall by Kasper Bosmans with white paint yet, but allow it to take on a different role as support for a copy of a magazine that displays less and less of Mia Farrow, by Melvin Moti. Four more works will be on display. There will be a lacquered apple by Voebe de Gruyter. Lacquer workshops do everything to avoid dust but De Gruyter convinced craftsman Zheng Chongyao to do exactly the opposite: take the apple outside to dry and allow the dust of days and nights in Fuzhou (China) to settle in as many layers of lacquer. The apple is a record.

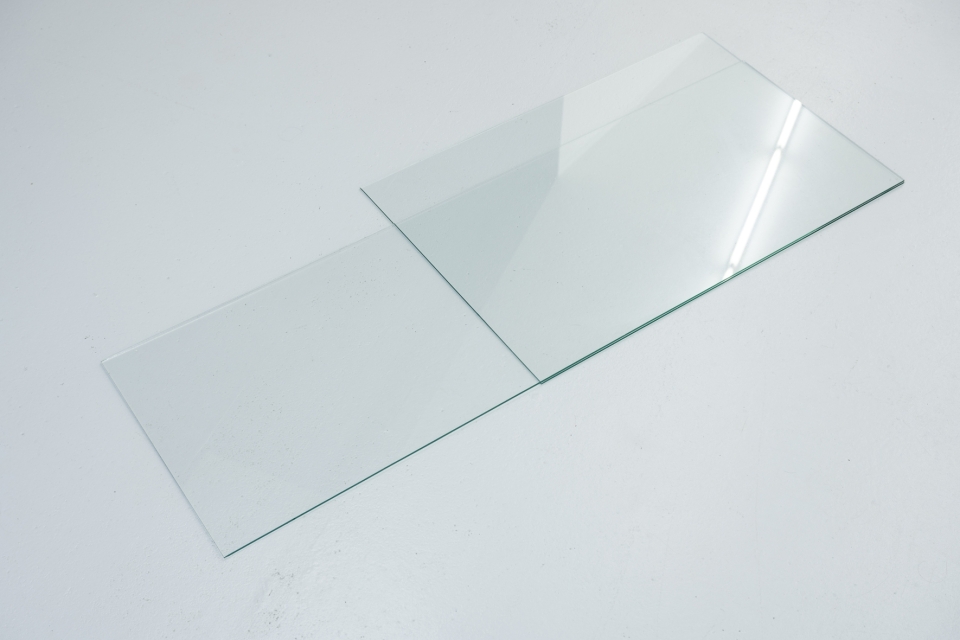

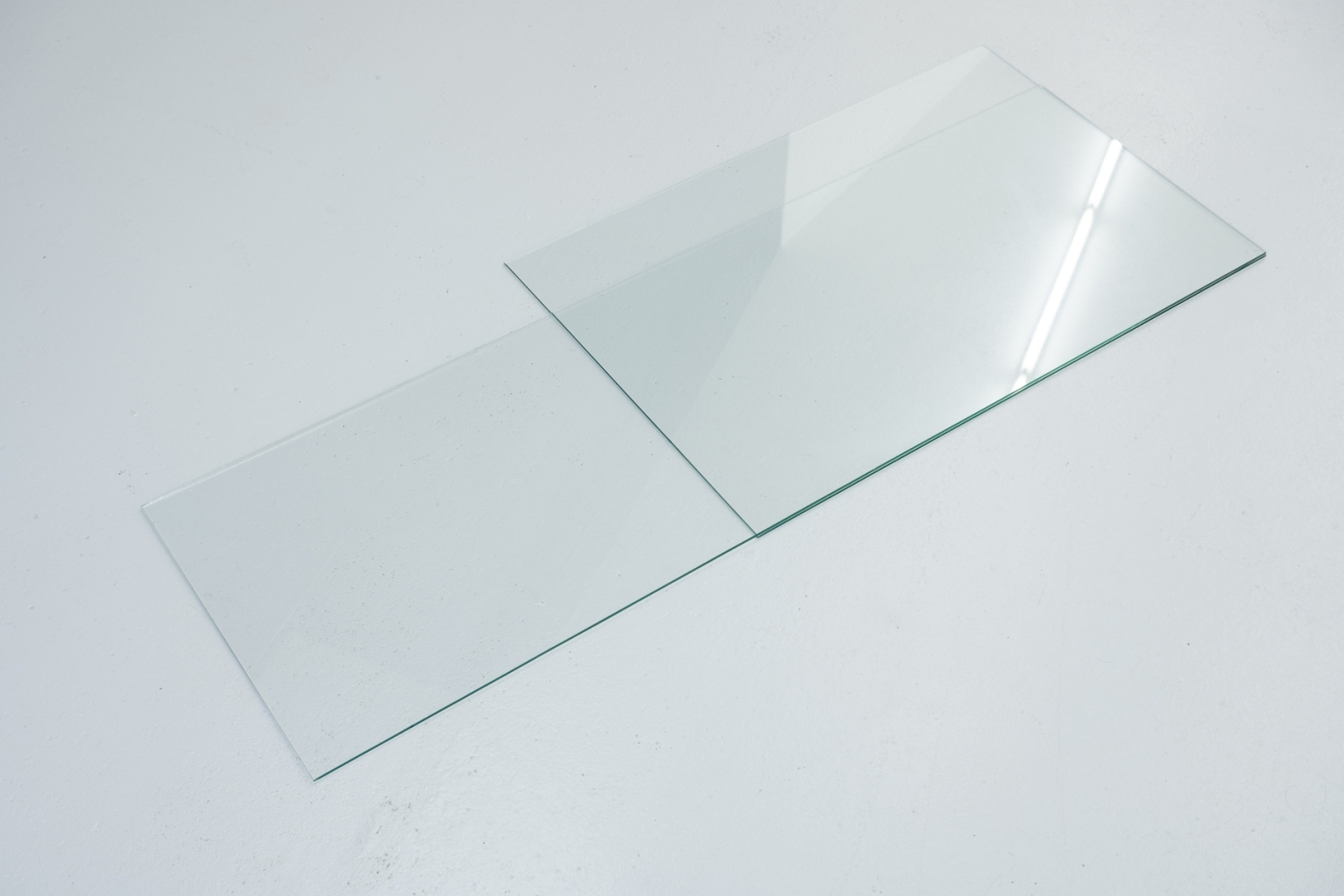

Then there is a drawing by Guy Mees, tiny pastel dots move towards the irregular edges of the paper, floating out of sight. A floor piece by Kitty Kraus that consists of two stacked sheets of float glass. The piece reflects the ceiling. Sharp, unpolished edges hold us back. Just as the exhibition opens, a room in Edgemont, North Vancouver in Canada will have been emptied and the door and windows closed. A publication with a conversation about this work between Daniel Gustav Cramer and gerlach en koop will be available and free to take.

A spatial intervention originally made by Gerrit Dekker for a group exhibition at BAK in Utrecht (2003), will be restaged in Rib In the absence of Gerrit Dekker. At the time the invitation interrupted a voluntary withdrawal from the structures of the art world but soon after he resumed his retreat that lasted until he died, October last year.

Daniel Gustav Cramer

In a chapter about the apartment in his famous book Species of Spaces, Georges Perec tries to imagine a space without a use. ‘It wouldn’t be a junkroom, it wouldn’t be an extra bedroom, or a corridor, or a cubby-hole, or a corner. It would be a functionless space. It would serve for nothing, relate to nothing.

“For all my efforts, I found it impossible to follow this idea through to the end. Language itself, seemingly, proved unsuited to describing this nothing, this void, as if we could only speak of what is full, useful, and functional.”1 Then, in the last part of this section, he says something difficult to grasp – something mysterious that we keep coming back to: “I never managed any- thing that was really satisfactory. But I don’t think I was altogether wasting my time in trying to go beyond this improbable limit. The effort itself seemed to produce something that might be a statute of the inhabitable”

In the beginning of the 1960s, Perec found a job as a documentaliste, or scientific archivist, at a big institution for sleep research. He stayed a long time – until 1978 – and although he got the position by chance, sleep became a recurring theme in his work.

Thinking about the Empty Room by Daniel Gustav Cramer, it occurred to us that Perec might actually be describing the impossibility of meeting his sleeping self.

Kasper Bosmans

The written instructions Kasper Bosmans gives to execute the mural No Water are very precise in some respects and very imprecise in others. All deliberate, of course. The specific hues for the blue and the brown and the height of their separation were to be decided upon by gerlach en koop. According to Bosmans the border between the two colours is not just a division; it is a horizon.

If you draw a line on a wall from left to right, saying ‘This is the horizon’ as the start of something – a story, a performance, a mural – then that line would only correspond to the real world for people who are exactly your height or, more precisely, people whose eyes meet yours exactly. This horizon would bind all of those people. Everyone else would see it as a representation of the horizon. They would follow along, but from an ever so slightly different perspective.

By drawing the horizon very low (say 60 centimetres) or very high (say 275 centimetres) we can be fairly sure that it will be a representation for everyone who visits the exhibition. For the paint gerlach en koop decided to approximate the brown hue in the eyes of a very specific person and the blue hue in the eyes of an equally specific other. They didn’t want to reveal the names when the work was executed the first time in Bremen, but could not keep their mouths shut then. So here they are, Andy Warhol and John Giorno, cameraman and protagonist of Sleep2.

Melvin Moti

A vintage LIFE magazine from 1967 with the actress Mia Farrow on the cover. For her role in the movie Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Roman Polanski asked Farrow to slowly lose weight to coincide with her mental dissolve, which is completely at odds with the weight increase one would expect from a pregnancy. The viewer sees how Farrow’s character turns into something gruesome simply by becoming paler and skinnier. Disturbance is implied not by excess, but by reduction.

The magazine is exposed to a lot of sunlight, thus repeating what happened in the movie, draining life from Farrow. And yet the blue of her eyes becomes brighter and brighter.

Miamilism can be defined as the perfectly ‘natural’ appearance of something that keeps the ‘natural’ unseen. It is a ‘vehicle word’ for the theatrical minimalism that is characteristically embodied by Mia Farrow. Farrow’s make-up in Rosemary’s Baby made it appear as if she had no make-up on, as if she were showing her most ‘natural’ face. But Farrow also visually blended into the background of the set, epitomising the manipulation of the seemingly ‘natural’ like no other silver-screen personality.

Kitty Kraus

To Fall Asleep

I’m falling asleep. I’m falling into sleep and I’m falling there by the power of sleep. Just as I fall asleep from exhaustion. Just as I drop from boredom. As I fall on hard times. As I fall, in general. Sleep sums up all these falls, it gathers them together. Sleep is proclaimed and symbolized by the sign of the fall, the more or less swift descent or sagging, faintness.

To these we can add: how I’m fainting from pleasure, or from pain. This fall, in its turn, in one or another of its versions, mingles with the others. When I fall into sleep, when I sink, everything has become indistinct, pleasure and pain, pleasure itself and its own pain, pain itself and its own pleasure. One passing into the other produces exhaustion, lassitude, boredom, lethargy, untying, unmooring. The boat gently leaves its moorings, and drifts.2

Voebe de Gruyter

A busy, two-lane road lined with trees in Fuzhou. Traffic noise drowns everything out. To the left are old wooden houses undergoing demolition; to the right is a construction site where new concrete apartment blocks are being built. The air is incredibly dusty and polluted, as it is in most Chinese cities. I not only smell the particles with every breath I take, I can almost taste them as well. Several people are trying to pick fruit from the trees with long sticks. I do not know what kind of fruit it is; I’ve never had it. They are shaped like apples, but hairy.

A row of shops lines the wide sidewalk. Large display windows show all kinds of lacquered objects. I enter one of the shops. The lacquer master offers me tea. Zheng Chongyao is his name. I look around. The space is really long and successive paper screens mark the space’s transition from shop to workshop. Several people are at work.

At the very back – about 30 metres from the street – is a room with water on the floor where no one is allowed to go. I am told that the lacquered objects dry here, where there is no dust, only to be re-lacquered 12 hours later. One layer per day, one per night. The whole process is repeated again and again, sometimes for weeks on end.

I step back out onto the street.

I am struck by the contrast.

I return to the shop a week later with apples sculpted from memory. I need all of my skills and charm to convince Zheng Chongyao to do something that goes against everything his workshop is set up for, and that is to take my apples outside to lacquer.

Each apple is a record.

Guy Mees

Verloren ruimte

In a conversation between herself, Wim Meuwissen (WM), Dirk Snauwaert and Micheline Szwajcer, Lilou Vidal (LV) says: Guy Mees approved a six-line text that defines Lost Space. You, Wim, had originally written the text in the 1960s as an introduction to a play, but the text was subsequently reworked by Willem-Joris Lagrillière, who was at the time a junior copywriter at an advertising agency. This sort of ghostwriting and appropriation of language raises the question of the author, the work, and intention, all issues that Guy explores throughout his trajectory.

LV: Can we read it, then, as a sort of anti-manifesto?

WM: Yes, though at first it was not called Lost Space but Ongerepte Ruimte, which translates as Untouched Space. A space that’s intact, virginal, tangential. I would like to show you a sketch I made for you that might help us understand where that comes from. This is the house Guy lived in on Keizerstraat. His children slept here, and maybe he did too. The kitchen and all of that were over here. That’s where he lived, but I’ve never been in there. He lived with incredible simplicity. And this space here was totally empty. It was an attic, entirely painted white. There was nothing there, nothing at all. Nothing but the 1830s architecture. Here you see the hallway leading to this white space, which was also totally empty, except for an armchair that he had covered with white fabric. And here was an Yves Klein table. That was all. Over here was a skylight that illuminated the blue table.

LV: It wasn’t his studio, just an unused space on the periphery of the domestic area?

WM: Right. And people would come to see it. A poet, for example, and other people I knew. Artists. That’s how Lost Space came into being. Guy and Lagrillière agreed on it, maybe, and I accepted it. Also, the text I wrote became … another text. It was no longer my reaction to the void. And because Guy didn’t write, the text became a manifesto for his work. You can call it an anti-manifesto if you want, but it is a manifesto nonetheless.3

The Lost Space is an adjoining space.

The Lost Space is complementary to present-day living space.

The Lost Space does not have a clear-cut function.

The Lost Space is space as utility object, in which bombast becomes more difficult, and tangibility easier.

The Lost Space is simply the body defined by shape, colour, taste, smell, and sound.4

In the absence of Gerrit Dekker

For the exhibition Binnen en buiten het kader (1970) at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Gerrit Dekker closed a gallery with two doors. There is a photograph documenting the work, the empty room photographed from the inside, from a very low vantage point. If you were lying on the floor and looked sideways, this is what you’d see there. Overhead light, walls covered in what appears to be, a parquet floor, the skirting board recessed, a single electrical outlet, lamps with an air vent next to them, and a closed door.

For Dekker, spending time in exhibition spaces was important. In a sense, his installations – though that term was not yet in use – are the result of performances without an audience.

We make a jump in time to 2003. Dekker is invited to participate in a group exhibition titled Now What! at BAK in Utrecht. His voluntary withdrawal from the structures of the art world had been going on for thirteen years. He hesitates but finally agrees to have a so-called sheet framed – a photograph depicting his collaborative partner Ben d’Armagnac leading him through the halls of the Brooklyn Museum New York – but also decides to make an intervention in the space. Large pieces of cardboard are taped to the floor, guiding the visitor from the entrance door to the exit door of the room in one straight stretch, subtly discouraging them from entering the room itself and see the sheet up close. In this work the closed gallery from 1970 strongly resonates, but if the connection was picked up at the time, we don’t know.

A few years later a solo exhibition in the same institution titled About no below, no above, no sides followed, after which Dekker pulled out permanently. This retreat, however, did not mean abandoning art: on the contrary. Although he no longer referred to himself as a visual artist, Dekker insistently kept engaging with aesthetic practice, exploring its various potentials in everyday life, according to BAK in their press release. Volunteering to help the homeless for example, in Arnhem where he lived, until his death, October last year.

- 1This and subsequent quote appear in: Georges Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces [Espèces d’espaces, 1974], translated from French by John Sturrock, New York: Penguin Books, 1997, p. 33–35.

- 2Jean-Luc Nancy, The Fall of Sleep [Tombe de sommeil, 2007], translated from French by Charlotte Mandell, New York: Fordham University Press, 2009, p. 1.

- 3About Guy Mees’, a conversation between Wim Meuwissen, Dirk Snauwaert and Micheline Szwajcer, conducted by Lilou Vidal, in: Guy Mees: The Weather Is Quiet, Cool and Soft, ed. Lilou Vidal, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2018, pp. 161–162.

- 4Guy Mees, ‘The Lost Space’, in: Guy Mees: The Lost Space, ed. Lilou Vidal, Paris: Paraguay Press, 2018, p. 18.

Lisa Ivory lives and works in London. Solo exhibitions include Beasts Beguiled, Museum of Witchcraft and Magic (Cornwall), Savage Gardens, Pamela Salisbury Gallery, New York, Vice, Malice, Lust and Cunning, Lubomirov-Angus-Hughes Gallery, London. Her work has been part of group exhibitions in London and overseas that include Ricco Maresca Gallery (New York), The London Art Fair (London), Charlie Smith (London), Saatchi Gallery (London), Fragment Gallery (Moscow) and Fabian Lang Gallery (Zurich).